Yesterday, I talked about a paper by the ECB that investigated the deglobalisation trend. There, I showed how deglobalisation is probably the wrong word because countries like the US do not decouple from international suppliers but mostly diversify their supply chains to reduce risks. Today, I want to discuss what the paper has to say about how this trend influences prices and inflation.

I have heard some economists claim that deglobalisation leads to lower prices because we are building new capacity and that new capacity is not met by additional demand so in aggregate, prices need to drop. One of the people who claims this would be the case is incoming US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, founder of Key Square Group, who wrote the following in his letter to investors at the start of 2024.

Excerpt from Scott Bessent’s letter to investors in early 2024

Source: Key Square Group

My immediate reaction to reading this was “what utter nonsense”.

First arguing with supply and demand is incredibly short-sighted and can only be made by someone who has read a couple of economics textbooks but has absolutely no understanding of how the real world works. In the clean world of econ textbooks, global supply and global demand can be matched without trade frictions, while the whole point of the current deglobalization trend is that it is caused by rising trade frictions.

Hence, if there is oversupply of factories that can make good X (i.e. semiconductors) that doesn’t lead to lower prices. Assume there is oversupply for semiconductor manufacturing because Western importers have diversified away from China to Southeast Asia and other countries. Then China has a massive oversupply of chip manufacturing companies and as a result, chips prices will drop in China. But that doesn’t mean semiconductor prices will fall in the US because the US has either introduced massive tariffs on Chinese imports or made it illegal to use Chinese semiconductors altogether. So no price decline in the US, end of story.

Even so, the price of goods does not only depend on supply and demand but also on the cost of production (again something that econ textbooks take as either zero or at best constant). In the past, we have moved semiconductor manufacturing to China for a good reason: It is much cheaper to produce them there than in the US, Europe, and other countries with higher unit labour costs. As I explained here, globalisation was deflationary. For every percentage point increase in the global manufacturing market share of emerging markets, producer prices in Europe dropped by about 3%. In the period 1995 to 2015, globalisation has on average reduced inflation by about 0.5% per year in Europe, according to my estimates.

But now, these people claim that deglobalisation will be deflationary as well?

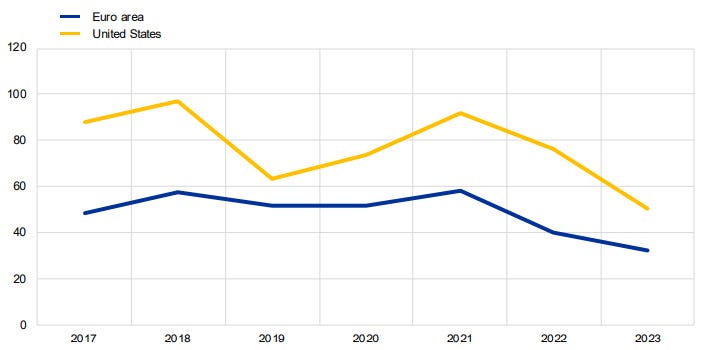

Let’s look at what happens as companies in the US and Eurozone diversify their supply chains. Here is a chart of the average price difference between a new sourcing country and the prices in the existing sourcing countries. In the US, prices from new sourcing countries tended to be about 80% higher than the prices paid to existing suppliers while in the Eurozone the price difference was typically in the order of 50%.

Price difference between new and pre-existing product-country flows

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

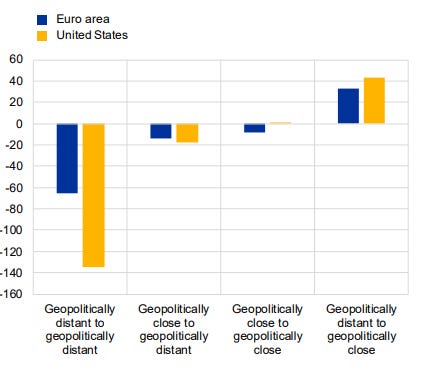

Next, let’s take the above chart apart by the kind of supply chain shifts made. The chart below shows the median price difference when moving from a geopolitically distant country like China to another geopolitically distant country like Vietnam, or a geopolitically close country like Mexico or Turkey. It also shows the shift in price when moving from a geopolitically close country.

Price difference between geopolitically distant and geopolitically close groups depending on the direction of the shift

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

It is immediately clear that lower prices are only available when shifting to geopolitically distant countries and it seems highly likely that any of these shifts are made to lower costs, not to derisk the supply chain. If a business shifts from a geopolitically distant to a geopolitically close country (friendshoring) the average price increase is about 30% for Eurozone businesses and more than 40% for US businesses.

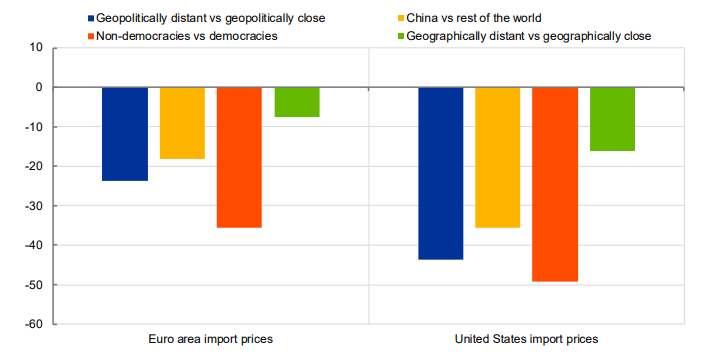

To conclude, here is a chart that shows the average price difference between geopolitically close and distant suppliers, geographically close and distant supplier democracies vs. non-democracies, and China vs. the rest of the world. If you look at this chart and the other charts in this post and still argue that deglobalisation leads to lower prices because increased supply is not matched by commensurate demand increases, then you have forfeited the right to be taken seriously, as far as I am concerned.

Differences between country groups in terms of import prices

Source: Ilkova et al. (2024)

Scott Bessent = The new King of Wishful Thinking

That second chart seems a bit odd. Is the Y-axis price change in percent? If so, how can the distant-to-distant price shift for the US be of minus 135%? Minus 100% would mean they’d get their goods for free, so … 🤔