The Virtuous Investor: Rule 4

Keep your goals always in sight – the virtuous investor dedicates all his efforts to his goals

This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“Let this be unto thee the fourth rule, that thou have Christ always in thy sight as the only mark of all thy living and conversation, unto whom only thou shouldst direct all thine enforcements […] and also thy business.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Two weeks ago, when discussing the second rule of the virtuous investor, I wrote about the importance to stick to your investment strategy and philosophy over long time frames in order to give it time to come to fruition. But buy and hold investing is easier said than done. Oftentimes, we lose faith in our investments when markets become volatile. There are different ways to stick to your investments over the long run, but one technique that I have come to appreciate a lot is goals-based investing.

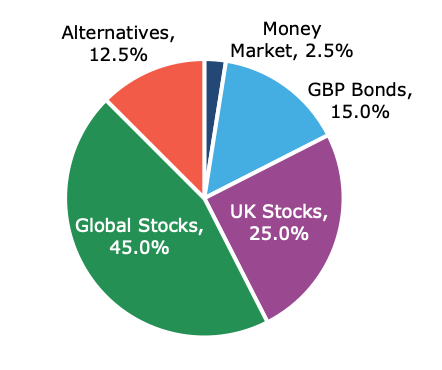

Take for instance the portfolio below, which according to Schroders represents roughly the average portfolio held by an investor in a UK defined contribution plan.

A typical UK growth portfolio

It is a rather typical growth-oriented portfolio with 70% equity and 30% fixed income and alternatives. Given that most investors have many years if not decades to save until retirement, it makes sense to have such a growth-oriented allocation in your DC plan.

The problem is, though, that when a bear market arrives, the losses in such a portfolio can be large and sticking to your investment strategy can be hard. Take a look at the returns of the portfolio around the time of the Global Financial Crisis (All returns are total returns in Sterling):

2006: +7.6%

2007: +6.6%

2008: -16.4%

2009: +16.0%

During the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) the portfolio lost up to 27% from its peak to its trough in early March 2009. Given these losses and even if we just look at the 2008 calendar year loss of 16.4%, it seems likely that some investors might have got cold feet and tried to abandon their strategy in favour of a more defensive one. Had they done so, they would have missed out on the strong performance of 2009 and 2010, when the portfolio would have recovered its losses (relatively) quickly.

How could the virtuous investor look at the portfolio differently? How could advisers have argued with investors to stick to their strategy even at the depths of the GFC?

Goals-based investing might provide an answer that helps. Instead of looking at the portfolio as a whole like we did in the pie chart and the performance numbers above, let’s structure the portfolio along the lines of the individual goals of the investor.

To do this, let’s leave the realm of defined contribution plans behind and look at our personal investment portfolios. For simplicity, I will work with my own situation as an example and take the growth portfolio I showed above as my own investment strategy. Now, my retirement is – unfortunately – still about 20 years away, so the portfolio has to be in place for at least that long and have a decent chance to grow until then. At the same time, I might need some cash from the portfolio in the short-term if I lose my job or if I have an unforeseen expense. Apart from that, it would be good if my portfolio would provide some regular income in excess of inflation to pay for upgrades on my house and garden.

Instead of looking at the portfolio as a whole, I split it up into three different buckets (or mental accounts) with different investment horizons corresponding to my goals:

The first bucket covers any unexpected cash flow needs if I lose my job, have an emergency or anything else. In this bucket, I put all my save investments and short- to medium-term bonds with a maturity of up to five years. The idea is that this bucket provides safety and allows the rest of my assets to remain invested for five years or more.

The second bucket is an income-producing bucket that is invested in conservative, low-volatility investments with some growth potential. The idea is that this bucket should compensate me for inflation and ideally create a little bit of excess income above inflation to fill up the first bucket, should I need to withdraw money from it or pay for renovations in my house etc. The investment horizon of this bucket is from year six until my retirement.

The third bucket is my pure growth bucket that contains all the risky, growth-oriented assets that I need to grow a nest-egg for my retirement. These are my equity investments. Ideally, this bucket will only be touched once I retire in 20 years.

Put together, the portfolio now looks like the chart below. I have assumed I have total savings of 1 million Sterling. Hey, one can dream…

The same portfolio expressed in investment buckets

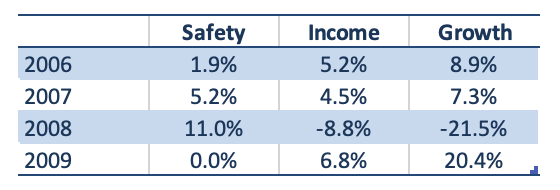

Let’s have a look at the performance of this portfolio in the same years as above:

Several things are apparent:

The safety bucket does exactly what it needs to do and shows positive returns in every year and an exceptionally large return in 2008. This provides me the assurance that in case of an emergency, I can still access my safety net without jeopardizing my long-term goals.

The income bucket provides solid returns above inflation in most years. During 2008 the bucket declines by 8.8%, which is substantial, but note that I have five years to recover from these losses. That is less than 2% return per year required to break even before the investment horizon of this bucket.

The growth bucket experiences major losses in 2008, but note how the portfolio is structured in such a way that everyone can see that the growth bucket has 20 years to recover from these losses. We are talking about 1% per year to break even and about 3% to 4% per year to break even in real terms after inflation.

It is much easier for me and indeed every investor to stick to the investment strategy if we can understand the purpose of each of the investments in the portfolio in terms of our own personal goals. This bucketing of the portfolio does exactly that.

Furthermore, this bucket approach also has the advantage that advisers can stop their clients from shifting funds out of cash or bonds into stocks in a long bull market or panic and sell their stocks at the height of a bear market.

Imagine an investor who sees the strong returns of stock markets of the last ten years and the low returns earned on government bonds these days. Many investors are tempted to reduce their cash holdings, or sell their bonds and invest it into stocks or alternative investments with higher return prospects. This is equivalent to selling the safety bucket in the portfolio. If a bear market strikes, this means that the investor has no safety net in place to cover any emergencies that may arise.

Similarly, if an investor wants to sell equities in a panic during a bear market, this is equivalent to reducing or eliminating the growth bucket in the portfolio. This means that the retirement nest egg will be smaller or won’t exist at all. Most investors are not willing to risk their retirement nest egg to feel safe in a bear market, especially not if they already have a safety and an income bucket in their portfolio.

Personally, I have used this bucketing approach with many private investors over the years and it is amazing how well it works in practice. And it really helps investors stick to their long-term strategy and come closer to the goal of becoming a virtuous investor.