I am a fan of the political project of unifying Europe and the European Union. There, I said it. But I know I am in the minority. I live in a country where a majority of the people decided in 2016 to leave the political project which is the EU. I work in the City of London where many are deeply sceptical of the Euro and the EU and expect its imminent demise. This leads to recurrent claims that the Eurozone is about to enter another crisis and the Euro is about to lose one or more of its member states, though admittedly, these claims have become rarer since the end of the European debt crisis in 2012.

For all those, here is my concession to you: I think the Euro in its current form is deeply flawed and if nothing is changed, the Euro will eventually cease to exist.

Where I disagree with the Euro Cassandras is in the assessment of how long the Euro can continue to exist in its current form and in the assumption that nothing will change and the Euro will inevitably cease to exist.

Let’s first look at the inherent flaws of the Euro and why it cannot go on like it is today forever.

In essence, with the creation of the Euro, the member states of the Eurozone gave up control over their monetary policy and entered a fixed exchange rate regime with other member states. At the same time, capital was allowed to flow freely between the members of the Eurozone. Economists will tell you that there is something like the unholy trinity that states that if a country has a fixed exchange rate and free capital flows with other countries to which its currency is pegged, it can no longer have an independent monetary policy. This is why we have the ECB which is in charge of monetary policy for all Eurozone member states.

But as we found out during the European debt crisis of 2011 and 2012, the unholy trinity extends not only to independent monetary policy but also to fiscal policy. If you have countries like Greece or Italy in the Eurozone, then reckless fiscal policy and excessive deficit spending can lead to all kinds of imbalances within the member states of the Eurozone and may even lead to the demise of the common currency.

There is a simple solution to this problem that is politically infeasible at the moment: Unify fiscal policy in a central government. This is why the United States and Switzerland work. These are countries which are a group of states that have banded together in a fixed exchange rate regime under a common currency. But to make that work, a central government ensures that individual states cannot enter into excessive debts. They do this by having a central government that ensures that major expenses like defence, social welfare and retirement systems are harmonised across states. It’s not possible to get a much better pension or much better welfare by moving from Alabama to California or from Zurich to Geneva. The system is roughly the same everywhere you go.

We could end all the talk about the flaws of the Euro and its demise by harmonising key fiscal policies across all Eurozone member states, but no Eurozone country is willing to give up its sovereignty and hand it over to a bunch of Brussels bureaucrats. But given the flaws in the Euro, I would argue that eventually this has to happen, and we have to create the United States of Europe or the Euro and the EU will crash and burn.

I can already hear readers claim that this will never happen, and it is indeed unimaginable for it to happen today, or at any time in the coming decades. I would argue it won’t even happen in my lifetime. But remember that many social projects were unimaginable and ‘will never happen’ until they did. Think of Catholics and Protestants living together peacefully or of black and white people going to the same school or eating in the same restaurant. Each of these events was supposed to lead to the decline of our society, yet we are still here.

Heck, if you asked the Brits in 1776 how long the American colonies would be able to survive on their own, they would have given the newly formed country a couple of years before they would be coming back into the warm embrace of the Empire.

The question is if the Eurozone can exist long enough for the political landscape to change and make the United States of Europe possible. This is tantamount to asking if the Eurozone in its current form can exist for another 50 or 100 years.

And my answer to that is: Likely, yes.

To see why, let’s have a look at the debt system of the Eurozone. That is something that over the last 15 years has become quite difficult because there are effectively three kinds of government debt in the Eurozone.

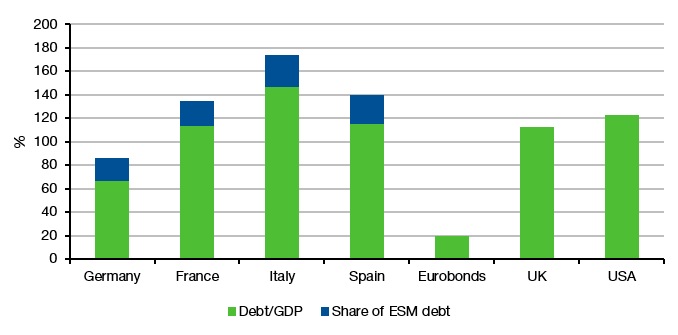

Traditional government debt. The chart below shows that Germany remains a standout performer here in the Eurozone with a debt/GDP-ratio of 66.6%. France and Spain are at 113.4% and 115.6%, respectively. These are debt levels similar to those of the UK and below the US. Only Italy has a substantially higher debt/GDP-ratio at 147.3%. 1. Note, I use general government debt, which includes the debt of local governments and government entities like infrastructure banks and the like.

One key outcome of the European debt crisis of 2011-2012 was the launch of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) through which countries like Italy can borrow. The trick of the ESM is that it is backed by all member countries of the Eurozone in case of a default, so credit risks are shared. However, in the unlikely case of a total collapse of the ESM, each country is only liable for its share of the debt, proportional to the country’s contribution to Eurozone GDP. In other words, if individual Eurozone countries default on their debt, the ESM can go to Germany, France, etc. to cover the shortfall, but only to a certain limit. The ESM bonds are thus only going to default if a large number of Eurozone countries default on their obligations. This is why there has been no European debt crisis since 2012 and why it is highly unlikely we will see a repeat of the debt crisis unless there is a major debt build-up in the Eurozone, which brings us to point 3…

In reaction to the Covid pandemic, the EU announced the creation of two rescue schemes. The Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) has a total volume of €98.4bn. The Next Generation EU plan (NGEU) has a total volume of €750bn. Crucially, though, the debt issued under these plans are true “Eurobonds”. Underwritten by the entire EU, they account for 18.9% of EU GDP. In case of a default of EU member countries, the key difference to the ESM is that every EU member country is fully liable for the entire amount of debt. It is effectively a last man standing rule which means that these bonds are de facto safer than any individual government bond or any ESM bond.

European debt levels

Source: Bloomberg

If you look at the Eurobonds issued during Covid, the debt/GDP-level of the Eurozone is ‘just’ 18.9%. I know, this is all a sleight of hand and accounting trickery because, in the end, that debt will have to be paid by the member states of the Eurozone, but if you hold these Eurobonds and Italy gets into trouble and defaults on its debt, do you notice anything? No, you don’t. If you hold Italian government bonds and Italy defaults on its debt, you lose your money. If you hold ESM bonds and Italy defaults, you get a haircut equivalent to Italy’s share in the ESM (17.6%). If you hold Eurobonds issued under the NGEU or SURE scheme you lose – nothing.

Obviously, if Italy were to default, one would expect markets to panic and start talking about a domino effect where the default of Italy will lead to the default of France and eventually all the debt (ESM, SURE, and NGEU) will end up on Germany’s shoulders. And there is no way Germany can pay all of that debt back. True, but I would argue that there are two backstops to this scenario.

First, the ECB could start buying the NGEU and SURE bonds in the secondary market to stabilise their prices and prevent them from defaulting. It’s what they threatened to do in 2012 and it ended the debt crisis then. Readers who argue that this cannot go on forever should read my instalment of government debt bombs and why monetizing debt via central banks can go on for decades without any problems. Why can the Bank of Japan successfully monetise debt for thirty years and counting without creating inflation or a default? If the Bank of Japan can do it, why shouldn’t the ECB be able to do the same thing?

Second, remember that we are dealing here with debt/GDP-ratios for individual countries and the Eurozone as a whole. But why do we talk about debt/GDP-ratios in the first place? We do this because the GDP of a country gives us an idea of how much income a government can raise through taxes. And these taxes can be used to pay off debt. So, if Eurobonds (NGEU and SURE) get into trouble, the EU could ask its member states to increase their contributions and if necessary, increase taxes on its citizens to pay the interest on Eurobonds. And since we are going to be in another crisis by that point anyway, why couldn’t we introduce European taxes levied by the EU directly on every citizen in its domain? Sounds awful, but never let a good crisis go to waste, as they say. And such a crisis could create the environment to harmonise fiscal policies between Eurozone member states and move towards the United States of Europe.

In other words, Eurobonds are covered by the power of the EU to tax the people who live in it. In that sense, we already have a United States of Europe when it comes to servicing Eurozone debt. And when we look at it this way, then a debt/GDP-ratio of not even 20% for the Eurozone as a whole isn’t so bad. With Eurobonds, the Eurozone can increase its debt load by several trillion Euros before even coming close to the debt levels of the UK or the US.

A rough calculation shows that thanks to the introduction of Eurobonds in 2020, the fiscal headroom for the Eurozone is about three to four once-in-a-century pandemics or ten to twenty global financial crises. And that should get us through the next 50 to 100 years without a problem. If anything, thanks to the accounting sleight of hand that are Eurobonds, the Eurozone looks like it is in a financially much stronger position than the UK, for example, which cannot push its debt problems on the people of other countries. Eurozone member states can and have. And will continue to do so with impunity for many decades if my calculations are correct.

"seize to exist" should probably be "cease to exist"?

As an Italian (and also a professional in the complex Italian tax system), I can confirm a couple of things that might be overlooked by non-Italians. Italy is a "fractal" piece of Europe, meaning that even after more than 160 years, economic differences persist from region to region, from north to south, just like in Europe, and even in terms of language. While Italian is the official language, countless dialects have survived, and if I move just 60 km to my wife's hometown, I can hardly understand what is being said in the local dialect. Nevertheless all doubts about the possibility of uniting a country with nothing unique have been brushed aside once it happened.

Second point: the resources obtainable through taxation. In Italy, the underground economy, and I'm not talking about organized crime, is still substantial and involves legal activities of professionals in all fields, businesses, and even private employment. I don't want to exaggerate, but in my opinion, a realistic estimate would be at least 20% more GDP than what is officially declared. So, while Italy may be the sick man of Europe in terms of debt, the introduction of new technologies (e.g., state blockchain for transactions) could be a good forced remedy. I hope I've been clear in expressing my point. Therefore, from my perspective, I am almost certain that the European Union will still be here when my children retire.