The government has too much debt, our deficits are too large, and this is all going to end in ruin through a massive debt default. That has been the rallying cry of fiscal conservatives for decades. I have a lot of sympathy for this rallying cry. After all, I am German, and we Germans are notoriously debt averse. Having more government debt means the cost of servicing this debt increases and that means that there is less money available for government investments, social services, etc. All this means there is less GDP growth. But it does not mean that the government will go bankrupt and default on its debt.

In fact, some time ago, a guy wrote about England and its unsustainable government debt. One of the main results of excessive debt in his opinion was the rise of inflation as paper money flooded the economy driving prices and wages up in the process. Furthermore, he was particularly worried about the fact that so much debt was held by foreigners who could use that debt as blackmail against the country. His conclusion was that the government would have to either raise taxes to pay for all that debt or default if it became too large.

That guy was the philosopher David Hume and he wrote that in 1764. It has been 260 years since he made that forecast and the debt of the UK government has grown exponentially since then, well beyond anything he or anyone else at the time could have imagined. Yet, today, the UK still is one of the very few countries in the world that has never defaulted on its debt, never had hyperinflation, and Sterling, while not exactly the world’s strongest currency is still one of the five most important and most traded currencies in the world.

This is a story that isn’t well known today, yet it clearly shows what I have talked about in the first installment of this series: What cannot happen, will not happen. If the consequences of an action are too extreme and too painful, people will find ways to turn away from the precipice and change course. The UK has done that for 260 years by changing policies that sometimes were more austere and aimed at reducing debt while being more spendthrift at other times. As a result, Hume’s forecast has been wrong for nine generations. How long do we have to wait before we admit that there might be something wrong with the ‘debt bomb’ argument?

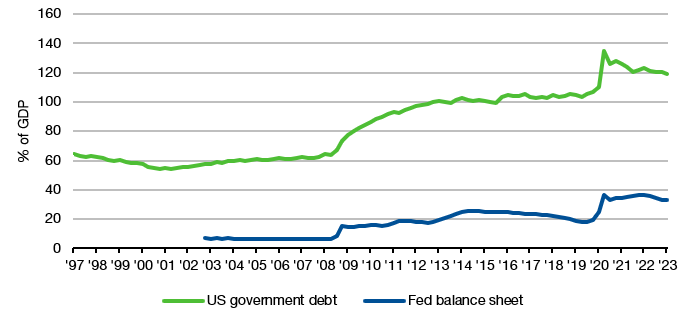

But let us get back to the present day and examine the example of the US (though we can do the same calculation for the UK or Eurozone). The chart below shows the growth in US public debt relative to GDP together with the growth in the Fed balance sheet relative to GDP. Clearly, debt has increased tremendously over the years. And thanks to the Fed’s QE programmes, the Fed balance sheet has increased in lockstep, reaching 33% of US GDP.

US public debt and Fed balance sheet relative to GDP

Source: Bloomberg

Yet, thanks to low interest rates, the cost of this rising debt to the US government has remained low and is indeed one third lower today than it was in the 1980s or 1990s (measured relative to share of GDP or tax revenue).

Interest cost of US public debt

Source: Bloomberg

But one may argue that low interest rates are a thing of the past and that going forward, the cost of servicing US debt will rise. To this, I refer readers to the previous instalment of this series where I discuss why interest rates cannot stay at current levels for long. The rising cost of government debt is just one more argument for why higher interest rates are a highly unlikely outcome in my view.

Of course, one possible outcome could be that investors lose trust in the US government’s ability to pay back its debt and thus demand a higher risk premium on long-term government bonds. This would be a development similar to the doubt about Greece’s ability to service its debt that triggered the European debt crisis of 2010 and 2011. As you may recall, this crisis was solved by the central bank buying government bonds in potentially unlimited amounts and artificially forcing long-term government bond yields lower to keep debt costs low.

And guess what, this is what the Fed could do as well, should investors start to demand a higher risk premium on US Treasuries.

Let me correct that. This is what the Fed has done for the last decade.

If you look at the first chart of this post, you will find that since 2008, the Fed’s balance sheet has grown in lockstep with government indebtedness. Though the Fed hasn’t explicitly monetised US government debt, it has effectively done so through its open market operations.

And this is where the case of Japan becomes relevant. I like to say that if you want to know our future, look at Japan. The Japanese government has a level of debt that should have led to a catastrophe long ago. Yet, they are still going, twenty years after Japan’s debt/GDP levels hit the heights the US has reached today. And if you are worried about the Fed’s balance sheet being large, take a look at the balance sheet of the Bank of Japan which is now not 33% of GDP as for the Fed, but 131% of GDP. The BOJ has been monetising Japanese government debt for three decades now without any negative consequence for government debt or without creating runaway inflation (in case you are wondering, Japanese inflation currently runs at 3%, compared to 4% in the US).

In fact, Japanese monetary policy is explicitly targeting 10-year government bond yields in order to keep long-term interest rates low and stimulate more demand and higher inflation. Without any success so far and few signs that this is going to change anytime soon. Growth and inflation remain stubbornly low in Japan despite the Bank of Japan monetising government debt for the better part of 30 years.

Japanese public debt and BOJ balance sheet relative to GDP

Source: Bloomberg

People who are expecting a debt catastrophe in the US have to explain, why the Fed could not do the same in the US as the Bank of Japan has done for decades there. There are commonly three arguments for why the case of Japan is a special case and why US government debt has to come crashing down.

The first argument is that monetising debt will lead to runaway inflation and hyperinflation. I have argued many times that this kind of quantity theory of money is nonsense (see here or here, for example). But even if you don’t believe me at that point, you have to explain why printing money for three decades has not created runaway inflation in Japan.

This is where people argue that Japanese government bonds are held mostly by Japanese people, not foreigners. Foreigners are more likely to lose trust and sell government bonds if they feel they are too risky. This is correct, which is why countries other than the US need to have fiscal discipline and cannot engage in reckless lending and uncovered deficit spending. The market turmoil after the UK’s mini budget under Prime Minister Liz Truss in September 2022 should be enough warning to governments around the globe that they cannot simply slash taxes and hope that this will create enough growth to offset the lost revenue. Governments have to provide a reasonable plan to show how deficits can be kept within limits.

This is why the EU enforces its stability criteria of a budget deficit no larger than 3% of GDP. But why can the US get away with much larger deficits for years and decades? Because it issues the world’s reserve currency and foreigners have to hold the US Dollar, whether they like it or not. As long as that is the case, foreigners will hold US Treasuries and not abandon them in any meaningful amount. And if you think that China could just crash US treasuries by dumping its holdings in the market or foreigners could abandon the US Dollar as a reserve currency, please read the instalment in this series on why that is complete nonsense.

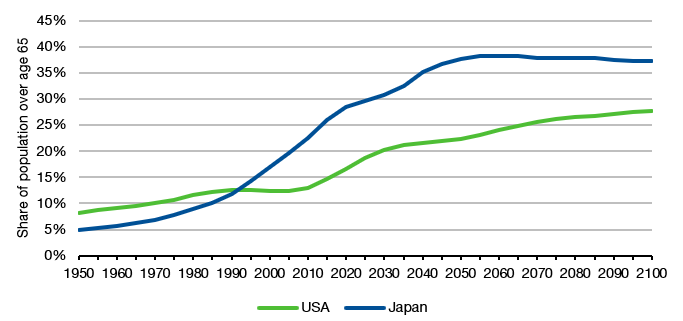

Finally, the third argument I hear a lot about why Japan can survive with massive debt loads without risking default is its demographics. The argument is that because the Japanese population is so old and old people hold more bonds, the demand for government bonds remains high and the government can always rely on having enough buyers for its debt. Well, the demographic challenges of Japan are enormous, but I would argue that the US and Western Europe don’t look that much different. The chart below shows the share of the population aged 65 and older. These are the people who are supposed to hold more bonds as a safe asset. Note how with the retiring baby boomer generation the US is now experiencing an explosion in old age population share and that supposedly means that the demand for US Treasuries will increase rapidly and remain high for decades to come.

Share of population aged 65 or older

Source: United Nations Population Division

To summarise, I find the arguments that the US is facing a debt bomb that will either lead to government default or runaway inflation very unconvincing. The example of Japan shows that much higher levels of debt than what the US or Western European countries have today can be sustained for decades, so if anything, a debt crisis is a very long time in the future. And the case study of the UK mentioned at the beginning shows that the day of reckoning may in fact be centuries in the future.

Central banks have and in my view will continue to monetise government debt to keep long-term bond yields low if they have to. People who are afraid that this may create runaway inflation have to explain why this was not the case in Japan over the last three decades. The ageing demographics in the US and Western Europe even help governments in keeping demand for their bonds high and reduce the need for central bank intervention. And in the US, there is additional support from the fact that the US Dollar is the world’s reserve currency and foreign investors have to hold US Treasuries, whether they like it or not.

It used to take 4.2 GBP to buy an ounce of gold. Now it takes 1503.

While I find some of your points to be valid shorter term, I would suggest that you do David Hume no justice. Not sure that your readers realise that one can default in nominal or real terms. Let's have an example: In 1750 Hume sells 2 500 "things" for 10 000 GBP in Sterling notes (or debt obligations, if you like). When Hume's descendants change these Sterling notes/obligations back into the "things", today in 2023, they get back seven (7) instead of 2 500. Or, 0,0028 % of its original value. I would call this a default. Greetings, Jens PS The thing is one ounce of Aurum.