This post is part of a series on The Virtuous Investor. For an overview of the series and links to the other parts, click here.

“Slippery verily and easy is the fall or descent into filthiness, but to return back again therehence, and to scape up onto spiritual light, this is a work, this is a labour.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam

In the last 21 instalments of this series on the virtuous investor, I have written about many rules to follow and techniques to implement that improve your performance. But the most important rule to remember of them all is this last one. It is to be honest and admit your faults to yourself and the people around you.

I have written about the value of investment diaries here and here, but what good does an investment diary do, if you are not honest with yourself about the mistakes you made in the past? How are you supposed to improve as an investor, if you cannot admit the mistakes you made?

I have written about the benefits of a financial plan and working with a professional financial planner to develop it here and here, but what good is a financial plan if you cannot admit that there are some goals you cannot achieve or that you have strayed from the plan and now need to make up for the shortfall?

Honesty and the ability to admit the limitations of one’s knowledge is crucial to improve as an investor.

And it is crucial for every professional adviser working with private investors. There is even an honesty premium to be earned as Uriel Haran and Shaul Shalvi have elegantly shown in a series of experiments with investors from the United States, the UK, and Canada. They were interested in the factors that make investors trust the advice they were given by professional advisers.

The problem with financial advice is that you do not know why an investor does or does not follow the advice given to her. Everyone knows that financial advice could be wrong and hence there is always an element of doubt in play when a client receives advice. However, there are two reasons why the advice given by a financial professional could be wrong. On the one hand, the adviser could be wrong because she does not know any better. She may give her honest best advice that may simply turn out to be wrong in the end. Or she could be biased in her advice due to an incentive structure that works against the client’s best interest.

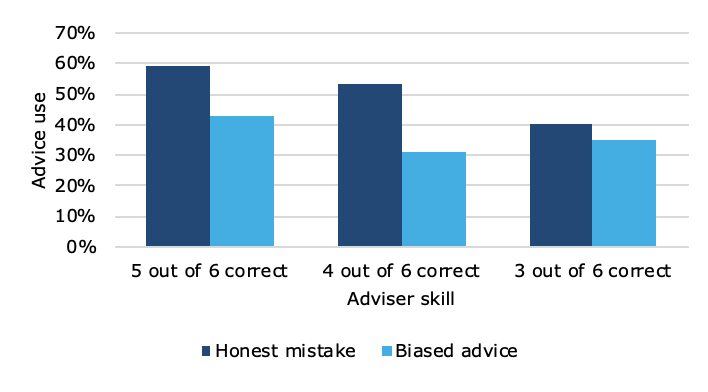

Haran and Shalvi examined whether clients trusted advisers more when they were perceived to be honest rather than biased. And guess what: To nobody’s surprise, clients trusted advice significantly less when they had reason to suspect it was biased. The chart below shows one of the key results of their experiments. They asked more than 200 investors to take advice from three different advisers. For each adviser, the clients knew that in the past they were more or less accurate, getting between three and five out of six recommendations right. However, in some cases, the clients were informed that the advisers made honest mistakes in their advice, while in other cases, clients were informed that advisers were incentivised to give advice that may not be in the client’s best interest.

The chart shows to what percentage the advice given influenced the initial intention of the investor. It is clear that clients who suspect that the advice given may be biased against them will follow the advice to a lesser degree than clients who think their advisers act in their best interest. Only when investors suspect that an adviser is useless and no better than chance (3 out of 6 recommendation correct in the past) did it no longer matter what incentives the adviser had.

Degree to which clients follow financial advice

Source: Haran and Shalvi (2019).

As an adviser, you can only make money if your clients trust you and follow your advice. But your clients are far more likely to follow your advice if you give honest advice and live up to your mistakes. One of the things that enraged me the most in my career was the unwillingness of banks and asset managers to own up to the mistakes they made in the financial crisis.

No company I know of has ever said to their clients: “We are sorry for the mistakes we made. We did the best we could, but we messed up.” Yet, this is exactly what they should have done to earn their clients’ trust. Instead, asset managers tried to find lame excuses how nobody could see the catastrophe coming and how it all wasn’t their fault for one reason or another. The term black swan probably only became famous in the first place, because it provided banks and asset managers with an easy scapegoat for their mistakes. If a crisis was unpredictable, how can your clients blame you for the mistakes you made in your advice and not having prepared them for the inevitable experience of a bear market? No wonder trust in banks and advisers has declined significantly over the last ten years. Would you trust someone who so obviously screwed up in the past but doesn’t have the spine to admit even the most obvious mistakes?

Back in 2009, my wife and I sat together and wrote a paper for the Journal of Wealth Management to show how trust can be earned by banks and asset managers and how trust can be recovered, once you screwed up. In my view, this paper is still one of the best pieces of research I have ever written, and I still go back to it time and again to guide my actions as an adviser (to see an example, how I did this in the past, click here). Yet, while I think this paper holds the secret to success for many struggling financial businesses, it is also one of the papers that have gained the least traction in real life. Banks and asset managers talk a big game about earning their clients’ trust, but if you look at their actions, most have done nothing in the past decade to earn that trust. And as we point out in our paper, actions speak louder than words.

So, please be honest with yourself and your clients and admit your mistakes. It is good for you, for your clients and for your business.